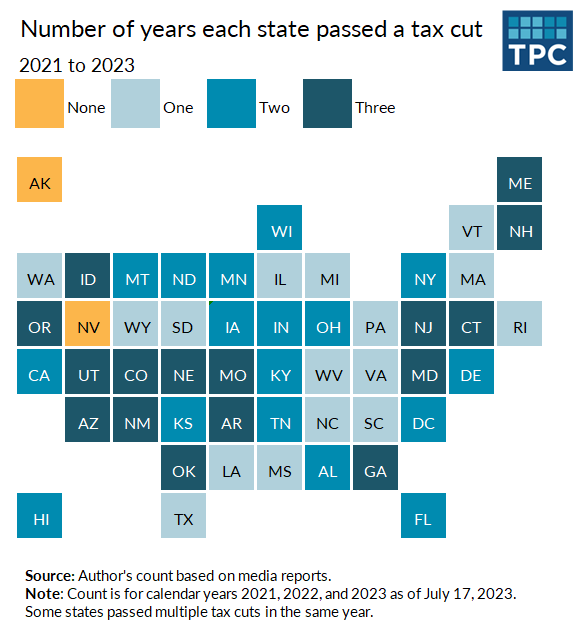

From the start of calendar year 2021 to today, 48 states and the District of Columbia have cut taxes. The only holdouts are Alaska and Nevada.

As I noted in reports summarizing state tax cuts passed in 2021 and 2022, this run of state tax cuts resulted from a mix of federal pandemic-related spending, a (previously) booming stock market, a lot of consumer spending, and other aspects of the post-COVID economy. The combination spiked economic growth, turbocharged state tax collections, and gave state policymakers large surpluses to spend on tax cuts.

As a result, different states passed different tax cuts for different reasons, but nearly every state—north, south, urban, rural, red, blue—cut taxes during the past three years.

Most states passed multiple tax cuts

Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia passed a major tax cut in two of the past three years, and 16 states enacted tax cuts in all three years. If anything, these are possibly undercounts because they are based on media reports, and smaller cuts sometimes make their way into a state’s tax code without garnering much attention.

States that enacted tax cuts in multiple years were not limited to one region or political party. Republican-controlled Georgia and Democratic-controlled Oregon both passed a tax cut in each of the past three years, while Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, and Wisconsin passed tax cuts in multiple years with politically divided governments.

In total, 29 states and DC passed a tax cut in 2021, 35 states and DC cut taxes in 2022, and 32 states (so far) have reduced taxes in 2023.

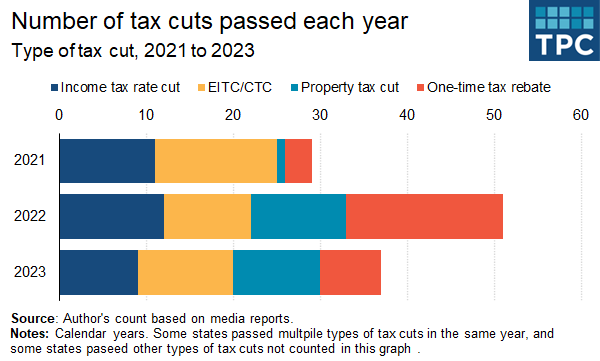

There was some change in the types of state tax cut passed from year to year

Looking at the specific types of tax cuts passed—not just states—reveals some areas of consistency and other sources of change over the last three years.

On consistency, individual income tax rates were reduced in 11 states in 2021, 12 states in 2022, and nine states in 2023. (Some same states reduced individual income tax rates multiple times; for example, Iowa cut income tax rates in 2021 and then further lowered rates in 2022.)

A similar number of states also enacted or expanded an earned income tax credit (EITC) or child tax credit (CTC) during each of these three years: 13 states and DC in 2021, nine states and DC in 2022, and 11 states in 2023.

Other tax cuts fluctuated in popularity. Only Nebraska cut property taxes in 2021, but 11 states passed property tax relief in 2022 and 10 states did so in 2023.

Meanwhile, 18 states sent residents a one-time tax rebate in 2022, compared with only three states in 2021 and seven states in 2023.

Although these tax cuts were the most common, it is not an exhaustive list. Many states also reduced business taxes and grocery taxes, and there were income tax cuts that did not involve a tax rate reduction or expanded EITC or CTC (for example, income tax relief for seniors was popular).

And as I noted in previous posts on state tax cuts, how a state chose to cut taxes (permanent versus temporary; rate cuts versus targeted credits) affects both who benefits and the long-term revenue cost.

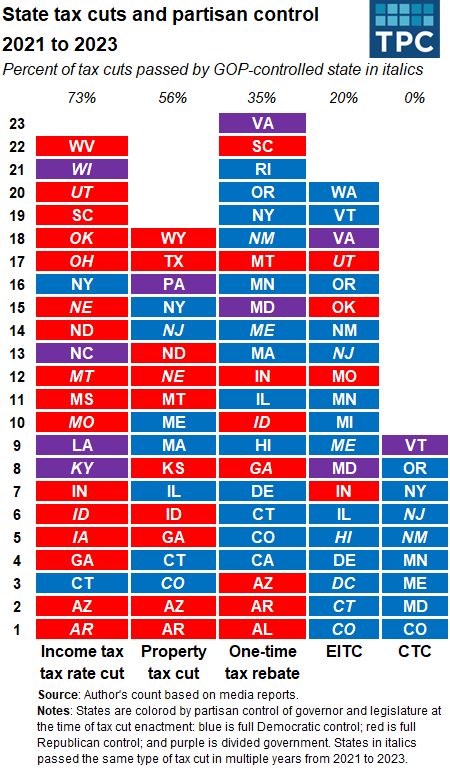

Political control affected the types of tax cuts enacted

Over the past three years, 17 of the 23 states that cut individual income tax rates were completely controlled by the Republican Party. Connecticut and New York were the only states with a Democratic “trifecta” to enact an individual income tax rate reduction.

In contrast, only four states—Indiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Utah—of the 29 states to enact or expand an EITC or CTC had a Republican trifecta. To a lesser extent, one-time tax rebates were also more popular in Democratic-controlled states than Republican-controlled states over the past three years.

Property tax relief was relatively bipartisan, though. Property tax cuts were passed in 10 Republican-controlled states, seven Democratic-controlled states, and one state with a divided government (Pennsylvania).

While some states are beginning to see state tax revenue slow, others (like Mississippi) are ready for another round of tax cuts. At this point, there is ample evidence for the pros and cons of various approaches. However, if and when the discussion turns back to tax increases, some states might have work to do.