In a famous conversation, the author F. Scott Fitzgerald is credited with saying that “the rich are very different than you and me,” to which Ernest Hemingway replied “Yes, they have more money.”

Our work highlights another key difference: the most affluent Americans not only have more income; they receive it—and pay taxes on it—in vastly different ways than the rest of us.

For policy makers concerned about long-term fiscal shortfalls and high levels of economic inequality, our work reinforces the notion that raising the tax burden on the wealthy requires a special focus on how those households gain wealth and skirt taxes. We highlight four ways to effectively raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans.

How Americans make money

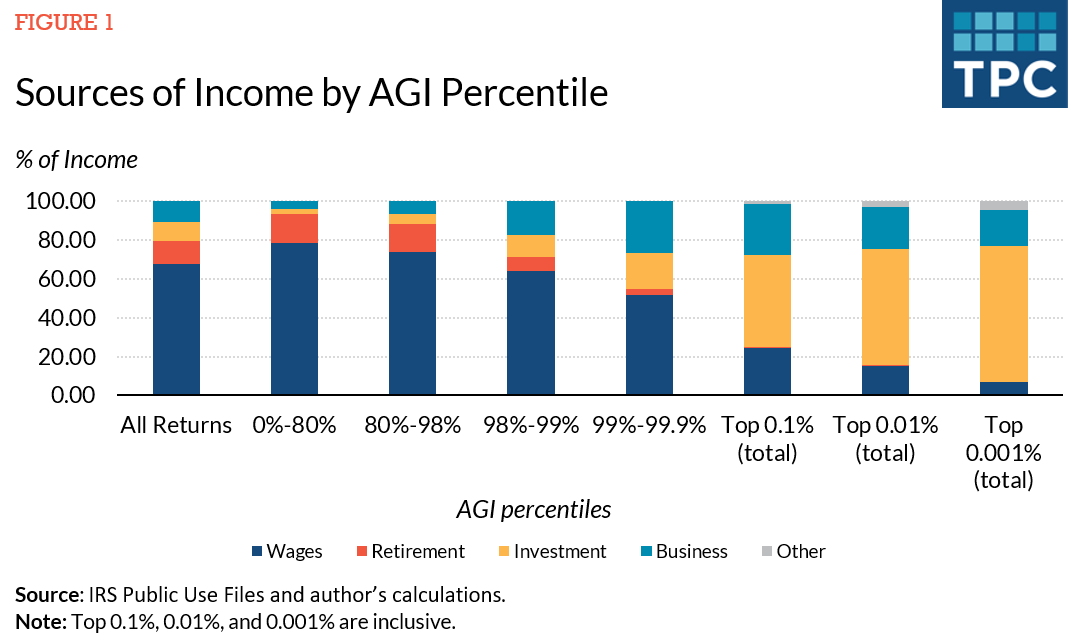

Most Americans receive almost all their income through wages and retirement income (pensions, 401(k)s, social security, and individual retirement accounts). The most recent available IRS data (2014) shows that wages and retirement income made up 94 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI) for households in the bottom 80% of the income distribution. Even for households in the 98th to 99th income percentile, wages and retirement income accounted for 71 percent of AGI.

At the very, very top, though, these sources are less important, accounting for just 15 percent and 7 percent of the income of the top 0.01 percent and the top 0.001 percent of households, respectively. These households receive most of their income from investments (interest, dividends, and especially realized capital gains) and businesses (including sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations). These items constituted 82 percent of income for the top 0.01 percent and 88 percent for the top 0.001 percent, compared to just 7 percent for the bottom 80 percent of households.

These patterns are robust over time and data sources. And in practice, the tilt toward capital income at the top is even larger than these figures suggest because AGI does not include the massive unrealized capital gains and very sizable inheritances that accrue to many affluent households.

How that money gets taxed

Wages face heavier taxation than capital income, even though wages go mainly to low- and middle-income households and capital income goes mainly to high-income households. Most federal revenues are collected from wages. Payroll taxes account for 33 percent of federal revenues and are imposed solely on wages. Income taxes account for another 52 percent of federal revenues, and studies show that the share of income tax revenues that derive from capital income is quite small. These studies were performed before the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, which further diminished the taxation of capital via special deductions for business and cuts in the top income tax rate, the corporate tax rate, and the estate tax.

Moreover, the highest effective marginal income tax rates on wages exceed 40 percent, whereas much business income is taxed at a top rate below 30 percent, dividends and realized capital gains are taxed below 25 percent, and unrealized gains are not taxed until they are sold. As a result, the tax share of income paid by the very highest-income households is often lower than for middle-class households.

How to fix it

There are many ways to raise taxes on the wealthy without harming economic growth. Here we highlight four options.

Capital gains reform may be necessary if policymakers want to increase tax burdens on wealthy households. The simplest policy here would be the elimination of the step-up basis at death. Heirs would pay capital gains taxes on the taxable basis of the decedent who acquired the asset, instead of the basis of the asset at death. In 2020, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) staff calculated that terminating step-up that year would raise $104.9 billion over the next 10 years. Alternatively, capital gains could be taxed at death, and treated as though the decedent had sold that asset. Batchelder and Kamin (2019) used 2016 JCT predictions to estimate that taxing accrued gains at death and raising the capital gains rate to 28 percent would raise $290 billion between 2021 and 2030.

Taxing intergenerational wealth transfers can make taxes more progressive and offset disparities in opportunity across income classes. Currently, less than 0.1 percent of all estates are subject to the estate tax, down from 7.65 percent in 1977. As baby boomers die, they are set to pass down $72.6 trillion in assets to heirs. Taxing these transfers more heavily would reduce inequality, increase opportunity, and raise revenues. The estate tax could be converted to an inheritance tax on recipients, with a reduced threshold of a million dollars for all gifts and inheritances (compared to the current threshold of almost $13 million) coupled with a tax rate that would equal the heir’s income tax rate plus some amount. This combined tax rate would integrate income and estate taxes. Since the heirs to wealthy estates are already usually in high tax brackets, the distributional impact would be similar to (though slightly less progressive than) the estate tax. This change has the political advantage of focusing on wealthy heirs, who were lucky enough to be the beneficiaries of wealthy relatives or friends, instead of targeting those who accumulated wealth.

Eliminating the Section 199A deduction for qualified business incomes would target another key component of income for the wealthy. The TCJA reduced the top income tax rate from 39.6 perecnt to 37 percent, and the deduction brought the effective rate on qualified business income down to 29.6 percent. In 2020, TPC estimated that the deduction would lower federal revenues by $417 billion over the following 10 years. The deduction is inequitable: TPC estimated that 55 percent of the direct tax benefits in 2019 would go to families in the top 1 percent of the income distribution and 26 percent of the benefits would go to the top 0.1 percent. Although the deduction was intended to increase employment and investment, the incentives for both are actually quite low given the complicated structure and non-targeted nature of the deduction. Additionally, its complexity creates an opening for business owners to reduce their taxes by re-arranging and relabeling their investments and expenses, a practice which is further incentivized by the increased difference between the effective tax rates on wages and business income.

A final option would be to create a value added tax (VAT) coupled with a rebate or Universal Basic Income (UBI). This would leave the net tax burden smaller or unchanged for most households but would impose higher tax burdens on the wealthy. Currently, wealthy households can finance extravagant levels of consumption without even paying capital gains taxes on the accruing wealth by following a “buy, borrow, die” strategy, in which they finance current spending with loans and use their wealth as collateral. By avoiding realizing their capital gains, they can avoid taxes at the same time they enjoy a luxurious lifestyle. A VAT would tax consumption and hence would force the affluent to pay taxes on their lifestyle, even if they did not pay much in income tax. A VAT of 10 percent, combined with a UBI payment of the federal poverty line times the VAT rate times two, would raise about $2.9 trillion over 10 years. TPC estimates that this system would be extremely progressive: after-tax income for the lowest quintile would increase by 17%, the tax burden for middle-income people wouldn’t change, and incomes for the top 1% of households would be reduced by 5.5 percent. The VAT would also function as a 10 percent tax on existing wealth, since future consumption can only be financed with existing wealth or future wages.

Conclusion

Each of these proposals would undoubtedly face significant opposition from those who benefit from the challenge of taxing affluent households: the wealthy themselves. However, in order to face the dual concerns of ever-increasing national debt and rapidly growing inequality, it is a challenge that we must take on before it’s too late.